Meaning of equilibrium#

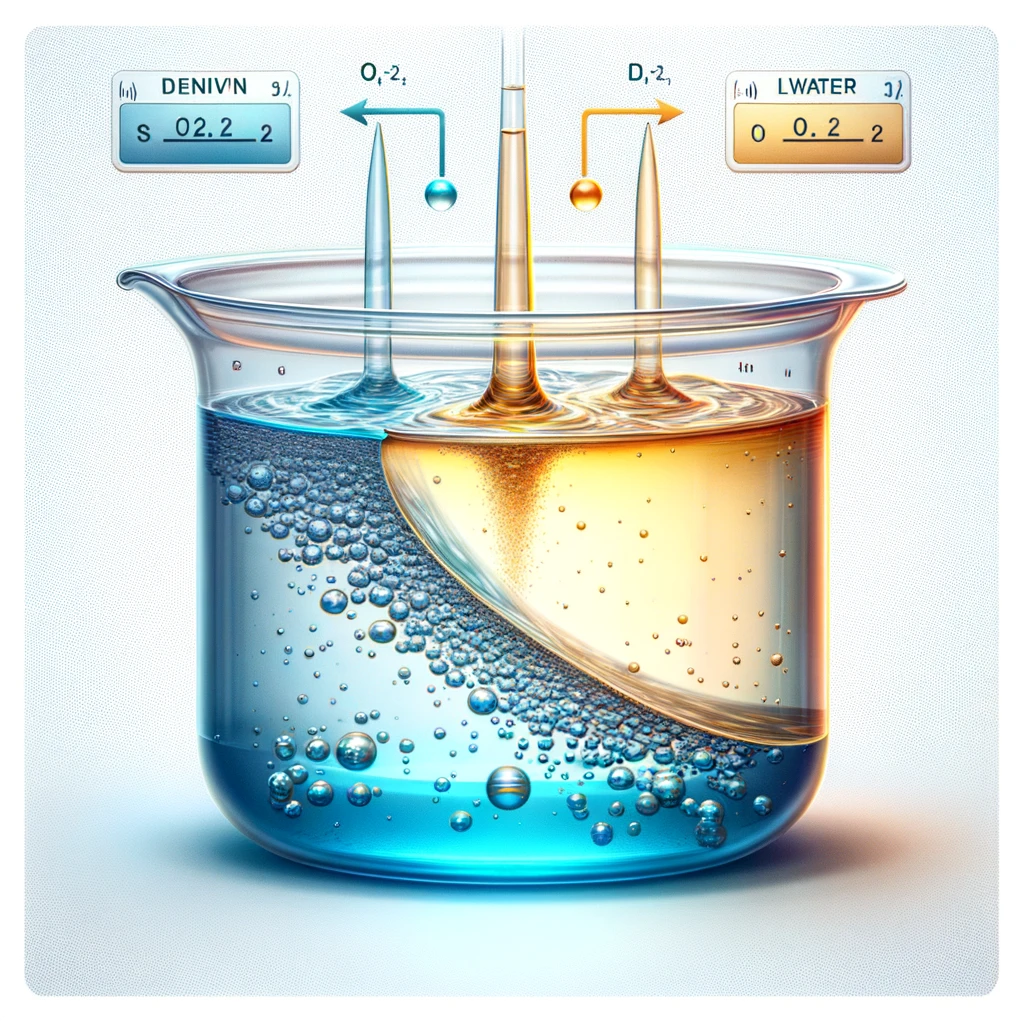

Since the Boltzmann factor \(\exp(E_S/k_\mathrm{B}T_R)\) strongly suppresses energies that are much larger than the thermal energy \(k_\mathrm{B}T_R\), one would think that system states with energies larger than \(k_\mathrm{B}T_R\) almost never occur.

No! Even if any particular high energy state occurs with very low (exponentially small) probability, it can be that we typically observe one of them if there are sufficiently many of them. What matters is not only the Boltzmann factor but also how many states the system has with a given energy.

To mathematize this insight, we introduce the multiplicity \(\Omega_S(E_S)\) of the system at energy \(E_S\). With that we can say that the probability to observe the system in a state with energy \(E_S\) is given by how many states with that energy exist times the probablity to observe one of them, i.e.,

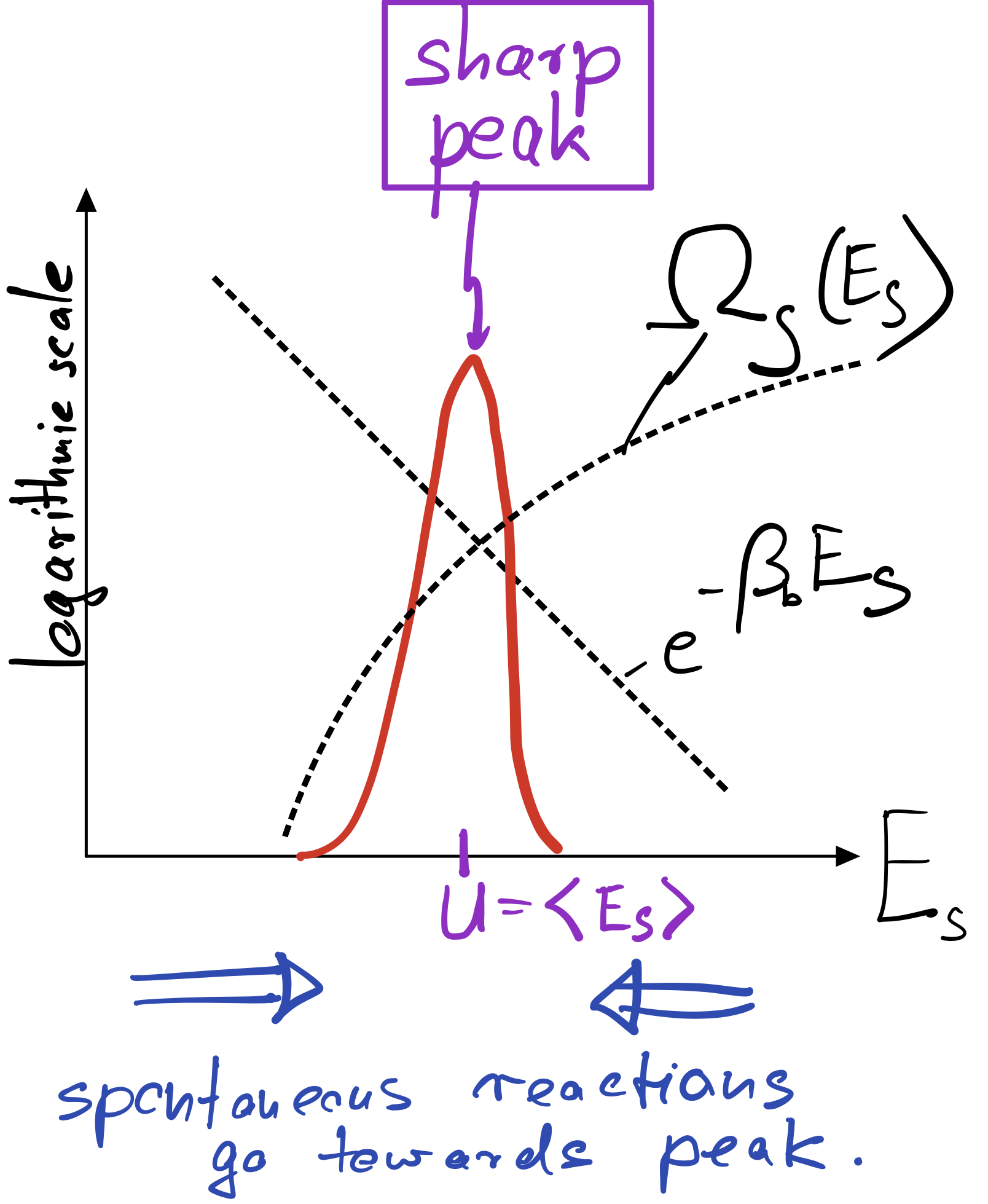

Usually there is a pronounced tradeoff between the two factors appearing in this equation. As the system energy increases, we gain a lot of new system states. But with increasing system energy, we also lose increasingly loose bath states, in fact at an exponential rate precisely given by the Boltzmann factor. The result is a pronounced peak of the product of both factors at a particular energy \(U\). This typical situation is depicted below.

In macroscopic systems, made up of O(Avogardo number) of particles, the peak becomes extremely sharp even in log space. In equilibrium, where our Basic Principle is satisfied, one therefore finds the system essentially deterministically at the energy \(U\) corresponding to the peak. That energy is called internal energy and can be found by maximizing the product of \(\Omega_S\) and the Boltzmann factor:

The internal energy can therefore be found graphically by following the trajectory of \(\ln \Omega_S\), which is concave (bending downward), until its slope equals \(\beta_R\).

In complete analogy to our definition of the temperature of the bath, \(\beta_R\equiv \partial_E \ln\Omega_R\), we now introduce the temperature of the system via \(\beta_S\equiv \partial_E \ln\Omega_S\). The above equation says that, at the peak, both temperatures have to be the same,

To make sure that the peak is actually a peak, we have to demand that the second derivative of \(\ln P\) is negative or, equivalently, that \(\partial_E^2\ln \Omega_S<0\). This condition is automatically met if \(\ln \Omega_S\) is a concave function, as sketched in the figure above.

To summarize: At equilibrium, large systems coupled to a bath are almost deterministically found at a particular energy, the internal energy, where the temperature of bath and system are equal.

If a large system is initially out of equilibrium, say it has a larger or smaller energy than \(U\), it will gradually move towards the internal energy as a result of its internal dynamics towards higher probability (towards the peak). This is indicated by the blue arrow in my sketch above, indicating that spontaneous reactions always proceed towards the peak. Any reaction going away from the peak, towards lower probability, requires some kind of work and would not happen by itself (more precisely, would occur only with very low probability).

Partition function#

To fully determine the probability \(P(E_S)\) to observe our system at a given energy \(E_S\),

we still need to evaluate a normalization constant \(Z\),

In large systems, the integral is dominated by the value of the integrand at the peak energy \(U\),

We define the Helmholtz Free energy \(F\) as

In the next section, we will see that the free energy generally attains a minimum at equilbrium. The above expression shows that \(F\) can be lowered either by lowering the energy or by increasing the entropy. The tradeoff between lowering energy (more states for the environment) and increasing entropy (more states for the system) is a recurrent theme in statistical physics.