Traveling waves#

Now that we have a basic understanding of the stochastic dynamics of growing populations, we would like to embed the population in space. In the simplest case, we can imagine that each particle is merely diffusing along a line, without any active motion in a certain direction. Then, when we start with one initial particle and \(R_0>1\), we will observe the expansion of the population both in density and range. Of particular interest is the shape and dynamics of the most advanced part of the population - the expanding population frontier. These fronts can serve as quantitative models of range expansions, epidemic outbreaks or evolutionary adaptation. Below we focus on the leading order behavior of the speed and shape of the fronts. Our treatment of number fluctuations is adhoc, but hopefully illuminating. Rigorous treatments of the asymptotic dynamics can be found in the literature[Hal11] Brunet Derrida, Igor, Kessler, Desai Fisher.

Once we allow the population to be distributed in space, we need a scalar field, the number density \(c(x,t)\) at position \(x\) and time \(t\), to describe the state of the population, rather than a single number (the total population size). This makes the problem infinite dimensional and, thus, very challenging in general.

Still, progress can be made in special cases, for example, in the absence of non-linearities, in which case the bulk of the population grows without bound, or in deterministic limits. It turns out, however, that both non-linearities and number fluctuations matter for a realistic description of traveling waves.

We will first ignore fluctuations entirely, incorporate dispersal and see what such mean-field theories would predict.

Incorporating dispersal#

Given a well-mixed model \(\partial_t N=s N\) for the net-growth of a population, the simplest way to include space is to say that the growth law applies locally and dispersal locally conserves particle numbers. Mathematically, this can be written as

where \(c(x,t)\) is the number density at position \(x\) and time \(t\). The second term on the right hand site is the one-dimensional divergence of a local particle current \(j(x,t)\), which represents the rate of chance of the number density of \(x\) due to local dispersal. When the current decreases with \(x\), densities must increase – hence the minus sign.

In the simplest case, we assume that the current is proportional to the gradient of the density,

Naturally the current goes from the high to low density regions – hence the minus sign. This ansatz corresponds to diffusion and represents a coarse-grained model of a population where individuals carry out unbiased short-range dispersal.

Local dispersal seems like a strong assumption. More generally, we may introduce a jump kernal \(K(\Delta x)\) representing the rate at which an individual jumps from \(x\) to \(x+\Delta x\). In that case, we may formulate the dynamics as follows

It turns out, the diffusion approximation is an accurate description on long time and length scales if the kernel is sufficiently rapidly decaying with distance. However, what “sufficiently short-range” means depends on the reaction term. For the case of no reaction, \(s=0\), one finds super-diffusive behavior, so called Levy flights, if \(K(\Delta x)\) has a diverging variance. With a reaction term, non-diffusive behavior occurs even if the variance is finite but strongly depends on the presence of noise (see slides).

Ignoring non-linearities#

If we ignore the non-linear population control and assume the growth rate \(s\) is strictly constant,

we can easily solve the ensuing reaction-diffusion equation. Namely, by substituting \(c(c,t)=\psi(c,t)e^{st}\), we can get rid of the reaction term and obtain a simple diffusion equation,

which we know how to solve. For example, if we assume localized initial conditions, we get a widening Gaussian with variance growing like \(2D t\). In terms of the number density, this solution reads

Although the solution has a well-defined peak, its tails extend to infinity. In any real simulation of discrete particles, there will instead be a most advanced particle.

We can try to estimate the position of the most advanced particle in an adhoc way by asking: “At what position will the density drop below some threshold density \(\epsilon\)?” This should occur for \(x>\ell(t)\) where \(c(\ell(t),t)=\epsilon\), yielding \(\ell(t)\sim v_F t\) where \(v_F\) is the so-called Fisher-Kolmogorov velocity,

Including population control#

By estimating the most advanced individual, we have just estimated an effect of the discreteness of the particles: There’s always a leading edge. Our answer for the asymptotic velocity of that leading edge is is even the asymptotically correct result for a branching random walk, whose first moment equation is linear and exactly given by (8).

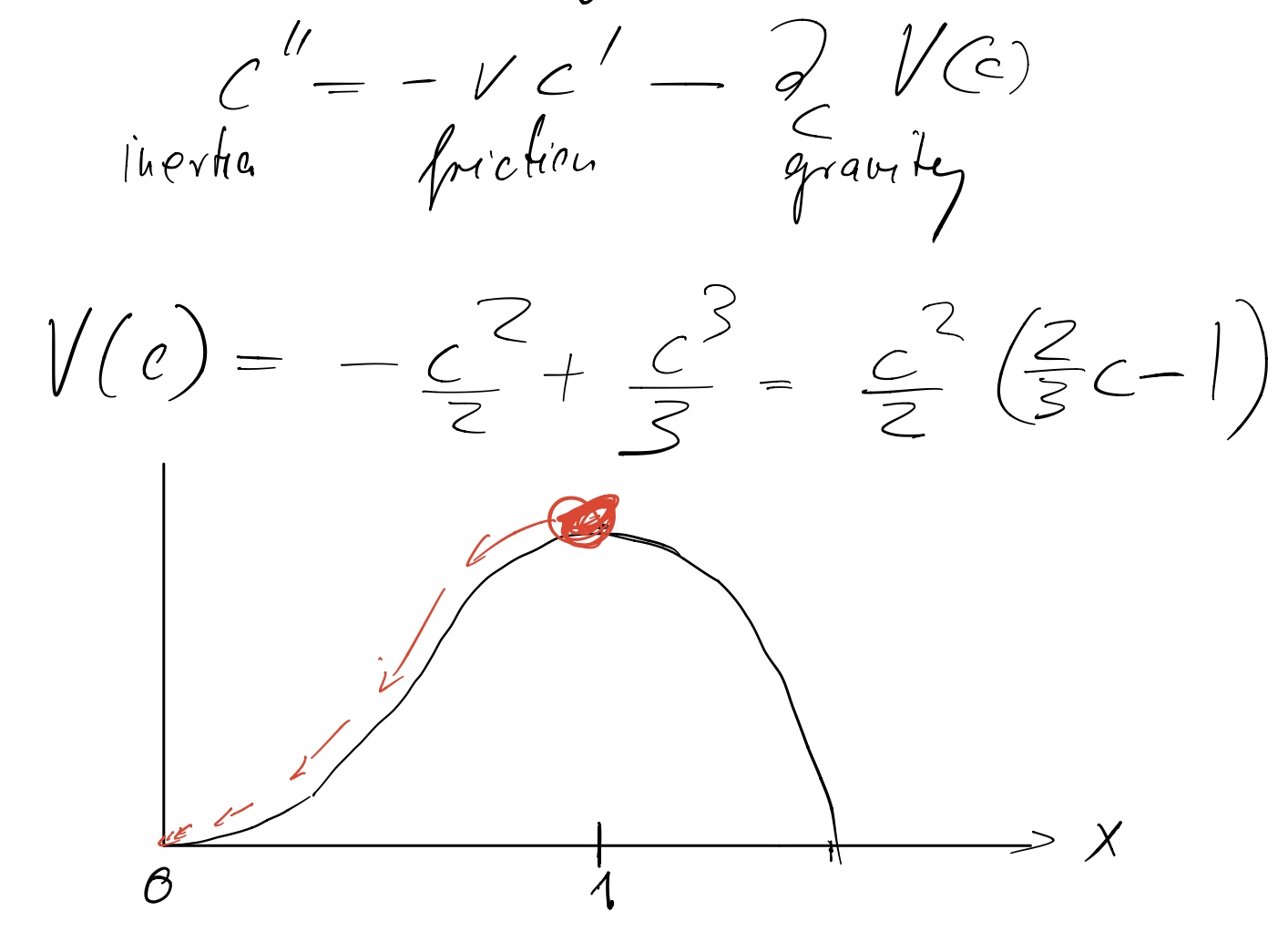

However, the linearized model has the unrealistic feature of an bulk population that grows without bound. To limit growth, we will now re-introduce non-linear logistic control, which yields the so-called Fisher-Kolmogorov equation,

Under this model, the population develops, after some relaxation time, a steadily moving wave train. In the co-moving frame, the population profile becomes steady,

In the tip of the wave, where \(c\ll K\), we can focus on the linearized version of this equation, which admits exponentially decaying solutions \(c\sim e^{-k x}\) where \(k\) satisfying \(D k^2-v k+r=0\). This quadratic equation has a solution with positive \(k\) only if the speed is larger or equal to the Fisher velocity \(v\geq v_F=2\sqrt{D r}\). Which of these velocities is realized however?

This so-called velocity selection problem requires some thought in general, but has an easy answer for localized initial conditions. In that case, we already know that the FKPP equation without non-linearity, which maps to the mean branching random walk, has a front that advances at speed equal to \(v_F\). Obviously, adding a negative term to the right side cannot accelerate the wave. Therefore, we can conclude that even the above non-linear waves travel, asymptotically, at the speed of the classical Fisher wave speed. Indeed, a more careful analysis shows that any initial condition with compact support leads to waves with \(v=v_F\) and to an asymptotic density profile \(c\sim e^{v x/2 D}\).

Fig. 1 Rolling ball analogy for the steady state equation describing the FKPP wave profile#

Different types of traveling waves

Waves are called pulled if the most advanced individuals have the largest growth rate. The ball analogy for those waves looks as in Fig. X a with a ball running down a hill onto a plane. Pushed and, more recently discovered, semi-pushed[BHK18] waves have reduced growth rates in the wave tip. The corresponding ball analogy is sketched in Fig. Xb, where a ball runs from one peak through a valley to a lower laying hill.

Effects of discreteness#

Our discussion of traveling waves ignored the fact that individuals are discrete. An exponentially decaying density can only make sense in an average sense when the density drops below one and that then implies the existence of fluctuations. It turns out these fluctuations crucial influence the behavior of waves.

One can show that the correct noisy version of the above dynamics requires to leading order on the right hand side of the FKPP equation a noise term of the form \( \eta(x,t)\sqrt{c}\) where the \(\eta\) is uncorrelated white noise, \(\eta(x,t)\eta(x',t')=\delta(x-x')\delta(t-t')\).

The FKPP equation (9) amounts to approximating \(\langle c^2\rangle=\langle c\rangle^2\). It turns out that this mean-field approximation is problematic. The velocity is reduced by a singular correction that cannot be obtained through perturbation analysis. More serious are the consequences for models of adaptation, which do not even have a finite wave speed in the mean-field approximation, and for the genealogical structures generated by these waves.

A lot of work has been done to implement the consequences of discreteness, most of them being adhoc at some level. Below I present an adhoc recipe that has given correct answers to leading order for many cases.

This method requires us to first extend our understanding of branching processes to space and introduce the concept of gene surfing.

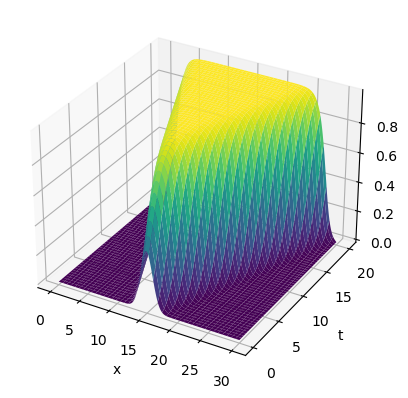

Simple code to simulate FKPP waves#

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Constants

D = 0.1 # Diffusion coefficient

a = 1.0 # Fisher-Kolmogorov parameter

L = 30.0 # Length of the domain

T = 20.0 # Simulation time

dx = 0.1 # Spatial step size

dt = 0.01 # Time step size

sigma0 = 1 # initial width

N0 = 1 # initial cummulative value

# Calculate the number of spatial and temporal steps

N = int(L / dx) + 1

M = int(T / dt) + 1

# Initialize the solution matrix

u = np.zeros((M, N))

# Set the initial condition

u[0, :] = N0/(sigma0 * np.sqrt(2 * np.pi)) * np.exp( - (np.linspace(0, L, N)-L/2)**2 / (2 * sigma0**2))

#u[0, :] = np.sin(np.pi * np.linspace(0, L, N) / L)

# Apply the finite difference method

for k in range(M - 1):

for i in range(1, N - 1):

u[k + 1, i] = u[k, i] + dt * (

D * (u[k, i - 1] - 2 * u[k, i] + u[k, i + 1]) / dx**2 +

a * u[k, i] * (1 - u[k, i])

)

# Plot the results

x = np.linspace(0, L, N)

t = np.linspace(0, T, M)

X, T = np.meshgrid(x, t)

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

ax.plot_surface(X, T, u, cmap='viridis')

ax.set_xlabel('x')

ax.set_ylabel('t')

ax.set_zlabel('u')

plt.show()

The above code is modified version of what ChatGPT gave me when I asked “write a simple python code to simulate a traveling Fisher Kolmogorov wave”:

This code uses a finite difference method to solve the Fisher-Kolmogorov equation with diffusion. It initializes a matrix u to store the solution at each time step. The initial condition is set as a sine wave, and then the finite difference method is applied iteratively to calculate the solution at each time step. Finally, the results are plotted using a 3D surface plot.

Please note that this code is a basic implementation and may not handle certain edge cases or optimizations. You can modify the parameters and experiment with different initial conditions to observe the behavior of the traveling Fisher-Kolmogorov wave.

Gene Surfing#

Taking discreteness into account is difficult in general. Forward in time, a branching process gives rise to a genealogical tree (show figure). Each time a birth event happens, a lineage splits into two, and both lineages have to be followed to describe the downstream dynamics fully probabilistically. That attempt is feasible if birth and death rates are constant but often impossible if they depend on the stochastic dynamics itself.

In these many-body problems of a branching tree, one can obtain a simpler single-body problem by taking a retrospective view: Sample one individual at the final time, i.e. a “tip” of the genealogical tree, and follow its lineage backward in time. A lineage traveling backward in time has the advantage that it neither splits nor ends, i.e. we only have to deal the degrees of freedom of just one particle. That can be useful if one knows the field of growth rates and used as a tool to enforce consistency of the dynamics.

To make this concrete, imagine sampling a particle of the a traveling wave and following it’s lineage backward in time. To describe the ancestral process of said lineage by the probability density \(G(\xi,\tau|x,t)\) that an individual presently, at time t and located at x, has descended from an ancestor that lived at \(\xi\) at the earlier time \(\tau\). In this context, it is natural to choose time as increasing towards the past, \(\tau>t\), and to consider \((\xi,\tau)\) and \((x,t)\) as final and initial state of the ancestral trajectory, respectively. With this convention, the distribution G satisfies the initial condition \(G(\xi,\tau|x,t)=\delta(\xi-x)\).

Notation

For space-time trajectories, we will use the convention that co-ordinates in greek letters \((\xi,\tau)\) refer to the starting point of the trajectory and those in roman letters \((x,t)\) refer to the end point.

Since a lineage cannot branch or end, all that it can do is to move around. If this movement is continuous and memory-less, we obtained a biased diffusion process. To describe this process, we develop a biased diffusion equation for the Greens function \(G\).

Since \(G\) is a pdf, it has to satisfy a continuity equation,

which simply ensures that the lineage is somewhere (conservation of probability). The probability current \(j(\xi,\tau)\) is given by

where the first term represents unbiased diffusion and the second part a deterministic bias with velocity \(v_*(\xi,\tau)\).

We have the mathematical form of the diffusion equation, but what’s the diffusivity and what’s the bias? A simple calculation shows that the diffusivity, \(D_*=D\) is the same as forward in time but that the bias is number density dependent,

In the co-moving frame, we expect the particle current to vanish

which predicts that the steady state distribution \(G(\xi)\) of the common ancestors is given by

where the pre-factor is fixed by the normalization condition, \(\int_\xi G=1\).

Using the mean-field solution \(c \propto c^{-v \xi/(2D)}\) of the FKPP, one finds that \(G\) should vanish everywhere because it is not normalizable.

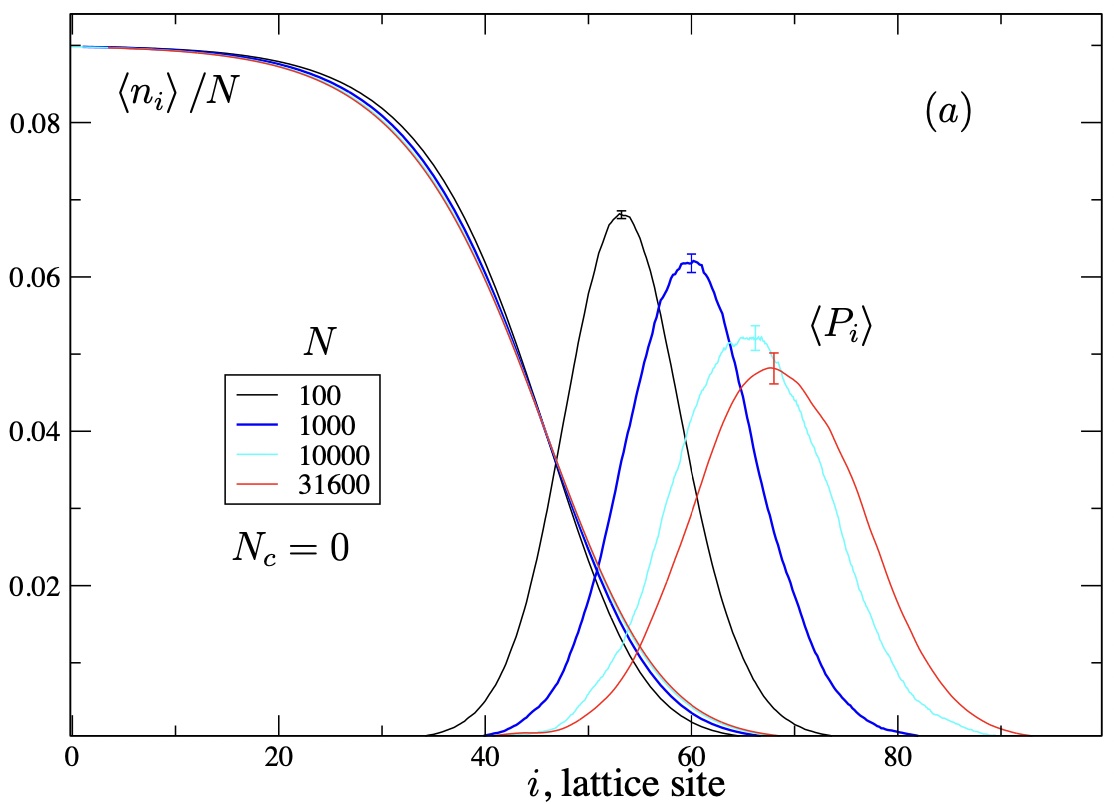

Fig. 2 Measured bell-shaped distribution \(G_\infty(\xi)\) as function of position \(\xi\) relative to the FKPP wave front (sigmoidal lines) for varying carrying capacities \(N\).#

But simulations of stochastic traveling waves show that this steady state distribution is a bell-like shape in the wave tip, see Fig. 2. Another hint that the mean-field solution to the number density is incorrect, in fact completely off.

Branching Random Walks#

It turns out that a more appropriate approximation to noisy traveling waves can be obtained from taking a particle viewpoint from the beginning.

One of the most extreme consequences of discreteness is that lineages can go extinct. In fact, when birth and death rates are nearly the same, the probability \(u\) of survival is very low, of order the relative growth rate difference \(s\). We arrived at this conclusion by deriving and solving a differential equation for the survival probability, which read

Generalizing this equation to the case of diffusion and spatially varying growth rates \(s(\xi,\tau)\), one obtains

Deriving this equation is a useful exercise, for which one has to retrace the same steps as for the non-spatial equation with the addition that one needs to account for the rates of dispersal. Notice that (12) has a similar shape as the FKPP equation.

In the frame co-moving with the wave traveling in the \(-x\) direction backward in time, we have

where \(s(\xi)=1-c(\xi)\) is given in terms of the density. To close this equation, we need an expression for the number density \(c\) in terms of the survival probability \(u\). Such a connection is provided by equation (10) for the distribution of common ancestors, once we recognize that

To see (13), notice that the probability that, at time \(\tau\), the common ancestor of future generations is at \(\xi\) is the same as the probability that any particle at \(\xi\) is going to survive forever, which is given by \(u c\).

Combining Eq.s (12), (10) and (13), we obtain

The third term on the right-hand side furnishes the major difference to the naive mean-field approach. One might think, at first sight, that this non-linear term can be ignored in the tip of the wave, where the density decays to 0 and \(c^2\ll c\). But the exponential amplification factor ensures that this factor becomes a leading order term sufficiently far out in the tip of the wave.

Consequences of tip fluctuations#

FKPP waves#

Assuming an overall decay \(c \sim N e^{-v x/(2 D)}\), it is easy to see that the quadratic cut-off term becomes of comparable to the first order terms when \(x_c \sim 2\ln(N)D/v\). For \(x>x_c\), the density decays faster, \(c\sim e^{-v x/D}\), just as if there is no growth beyond \(x_c\). I.e. the leading order effect of the fluctuation-induced term is to introduce a growth cutoff at \(x_c\). Therefore, the linearized equation

has to be solved between \(x=0\) and \(x=x_c\). To do this, it is convenient to introduce the variable transform

through which (15) is transformed into

which has a Hermitian operator on the RHS. (17) has the shape of a Schroedinger equation in imaginary time. The non-linearities of the original equation (14) effectively generate two absorbing boundary conditions for \(\phi(x)\), one at \(x=O(\ln N)\) and one at \(x=O(1)\).

We can solve equation (17) subject to these boundary conditions in terms of normal modes. To ensure a steady state in the co-moving frame, we have to demand that the ground state (lowest mode) has vanishing energy. All higher modes have higher energy, and therefore decay over time. The higher the mode number (the more nodes the eigen function has / the more rapidly it varies in space) the faster its relaxation to 0. Since the growth rate is constant between the two absorbing boundaries, we essentially have the mode spectrum of a particle in a 1D-box, which are cosine modes.

To fix the wave speed, we focus on the ground state,

which solves (17) at steady state (\(\partial_t \phi=0\)) if

implying that

Solving this equation, we obtain to leading order

So, the cutoff leads to a reduction of the wave speed, which only slowly vanishes as \(\ln N\) goes to infinity. In particular, it cannot be captured by a perturbation theory in the noise strength \(N^{-1}\).

The consequences of the cutoff on genealogical processes are even more pronounced. Without going into the details, we merely argue intuitively here. Due to the the second cutoff, lineages are localized on a scale \(\ln N\) and caused to coalesce on a time scale \(T_c\sim \ln^3 N\), which diverges when \(N\to \infty\).

Fitness waves#

Traveling waves not only occur in real space. They are often used to describe how the distribution of a trait, such as growth rate, height, strength etc. across a population shifts over time in response to a changing environment or in response to self-organization. The most classical of these waves is a wave of adaptation, where growth rate, or fitness, shifts towards larger values in response to the occurrence of fitter types (due to mutations) and their take over within the population.

A simple model to describe this situation is

where it is assumed that beneficial mutations all beneficial mutations have the same fitness effect \(s\) and occur at rate \(U\). The overline represents the population mean, \(\overline{f_n}\equiv \sum_n c_n f_n\), so that \(s\overline{n}\) is the mean fitness.

Two simple arguments constrain the leading order speed of these waves.

Adaptation speed depends on fitness variance#

Multiplying (18) with \(s(n-\overline{n})\), integrating over \(n\) and averaging over the noise yields

i.e. the rate of increase in fitness (LHS) equals the variance in fitness (RHS), or

When R. A. Fisher stumbled over this simple observation, he was apparently so excited that he called it “the fundamental law of natural selection”, although it was soon shown that this equation is neither fundamental nor a law.

The tip of the wave#

The density profile in the co-moving frame looks, to a good approximation like a Gaussian. But, because of the discreteness of individuals, this Gaussian has to be cut-off at the fitness value \(q\) of the most fit individuals. This tip of the wave can be estimated from \(e^{-(q s)^2 /(2 \sigma^2)}N\sim 1\) giving us

At the wave tip, we can estimate how long it takes for the next bin to be established, by

giving us

Self-consistency#

The wave speed \(v\approx \sigma^2\) to be consistent with the weighting time \(T\), we have to demand \(s/v\sim T\), implying

Note that, for these types of waves, number fluctuations not only cause a correction to the wave speed. Without taking fluctuations into account (\(N\to\infty\)), the wave speed diverges, as it turns out, in finite time.

Naive expectation#

Yet, the wave speed increases very slowly with population size, namely just logarithmically. According to classical population genetics, one would expect a linear increase, \(v= U N s\), based on the following computation. New beneficial mutations arise at a rate \(U N\), and each one of those mutations has a survival probability of \(s\). What’s wrong with that computation? Respectively, when is this computation correct?

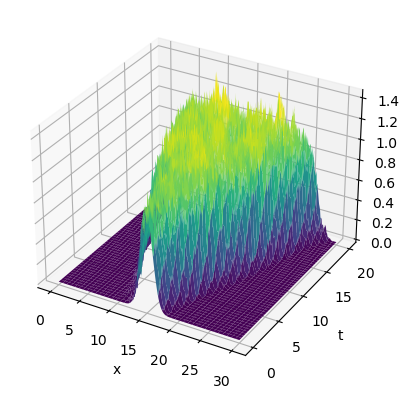

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Constants

D = 0.1 # Diffusion coefficient

a = 1.0 # Fisher-Kolmogorov parameter

L = 30.0 # Length of the domain

T = 20.0 # Simulation time

dx = 0.1 # Spatial step size

dt = 0.01 # Time step size

noisestrength = .001

sigma0 = 1 # initial width

# Calculate the number of spatial and temporal steps

N = int(L / dx) + 1

M = int(T / dt) + 1

# Initialize the solution matrix

u = np.zeros((M, N))

# Set the initial condition

#u[0, :] = N0/(sigma0 * np.sqrt(2 * np.pi)) * np.exp( - (np.linspace(0, L, N)-L/2)**2 / (2 * sigma0**2))

u[0, :] = np.exp( - (np.linspace(0, L, N)-L/2)**2 / (2 * sigma0**2))

#u[0, :] = np.sin(np.pi * np.linspace(0, L, N) / L)

# Apply the finite difference method

for k in range(M - 1):

for i in range(1, N - 1):

u[k + 1, i] = np.random.poisson((u[k, i] + dt * (

D * (u[k, i - 1] - 2 * u[k, i] + u[k, i + 1]) / dx**2 +

a * u[k, i] * (1 - u[k, i]))) / noisestrength) * noisestrength

# Plot the results

x = np.linspace(0, L, N)

t = np.linspace(0, T, M)

X, T = np.meshgrid(x, t)

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

ax.plot_surface(X, T, u, cmap='viridis')

ax.set_xlabel('x')

ax.set_ylabel('t')

ax.set_zlabel('u')

plt.show()

Speed of adaptation

The speed of adaptation scales with the log of the population size, much slower than naively expected (based on sequential selection) yet still diverging if number fluctuations are neglected (\(N\to \infty\)).

Comment#

Why do we prefer equation XXX with the emerging cutoff over equation YYY? Both treatments are approximate and uncontrolled by a small parameter.

The primary reason is the nature of the assumptions being made. The naive mean field theory assumes that growth rates are given by \(r(1-\langle c\rangle)\). By contrast, the gene-surfing-based theory is based on knowing the mean of the log, \(\langle v_* \rangle = 2 D \partial_x \langle \ln c\rangle\). The log of a quantity usually fluctuates much less than the quantity itself. The flaw of this intuitive argument is, however, there are realizations where the density drops to 0 at any x, which should dominate the mean of the log. To the rescue comes the fact that we need the quantity \(\partial_x \ln c(x)\) only if a lineage is actually present at \(x\), so that it can be sampled. Thus, we if we interpret the average \(\langle \ln c(x)\rangle\) as conditional on a lineage being present at \(x\), a divergence is prevented.

Well, if such hand waving still leaves you uneasy, there is a way to formulate non-linear noisy waves with a closed first moment[Hal11], which gives rise to the exact same cutoff as in Eq. XXX except for a factor of \(2\)! This method can be generalized to obtain models that, for any integer \(n\), have a closed set of \(n\) moment equations[HG16].

Problems#

Estimate the speed of a FKPP wave traveling down a narrow corridor of width \(W\). Assume the walls of the corridor to be absorbing.

Use the analogy of traveling waves to imaginary time Schroedinger equation to make predictions about traveling waves that involve standard solutions of quantum mechanics problems you know (using e.g. tunneling, defects, etc.).

Simulate an FKPP or fitness wave with finite particle numbers and measure speed and wave diffusion as function of \(\ln N\)

Extend the theory of branching random walks to offspring distributions with diverging moments.

Citations#

Gabriel Birzu, Oskar Hallatschek, and Kirill S Korolev. Fluctuations uncover a distinct class of traveling waves. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(16):E3645–E3654, 2018.

Michael M Desai and Daniel S Fisher. Beneficial mutation–selection balance and the effect of linkage on positive selection. Genetics, 176(3):1759–1798, 2007.

Oskar Hallatschek. The noisy edge of traveling waves. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(5):1783–1787, 2011.

Oskar Hallatschek and Lukas Geyrhofer. Collective fluctuations in the dynamics of adaptation and other traveling waves. Genetics, 202(3):1201–1227, 2016.